Fireworks thump hard into the springtime night sky. It is dark. No starburst of colour is visible in the smooth velvet stillness. Occasional light illuminates in patchwork shadows, finding pockets of space crushed between the city buildings which reach up to obscure all horizons. Noise booms through the warm evening air. There have been fireworks sounding most evenings this week. The holy festival of Diwali has been celebrated here – a time, when it is said, the goddess Laksmi visits homes to bring happiness and prosperity during this Festival of Light. There are fairy lights blinking in some of the frangipani trees in nearby apartment gardens, pinpricks of yellow colour flashing light in the dark. Outside my window, the city itself is quiet. An easterly wind moves through the branches of trees, bringing hot desert air from the Goldfields towards the metropolis. Some of the skyscrapers have coloured neon lights; mainly logos and names – some are just illuminated facades. Crickets sound. A full moon is forecast within a week, but as I write no moonlight is visible within the cosmos (yet). And then, for some reason, I think of the description of the moonless night given by the First Voice in Dylan Thomas’ play for voices, Under Milk Wood:

It is spring, moonless night in the small town, starless and bible-black, the cobblestreets silent and the hunched, courters’-and-rabbits’ wood limping invisible down to the sloeblack, slow, black, crowblack fishingboat-bobbing sea.

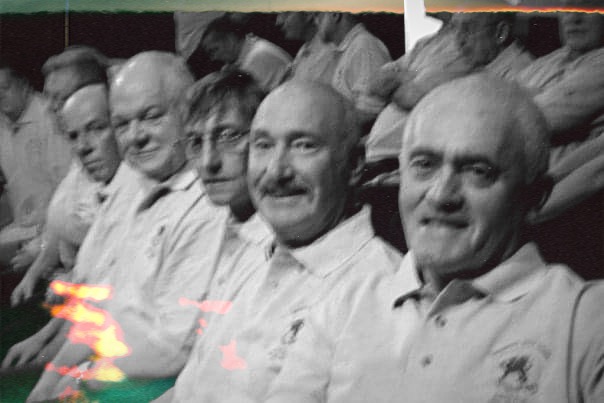

I think of home. Being a migrant on the other side of the world is a curious existence to have. It is both transient and of belonging to other places simultaneously (the old and the new). It is an existence between things; of being changed forever, almost in limbo. Sometimes caught in a concussion of cultures, languages and other identities. Looking in this box tonight I found a small folder of photographs, titled: Treorchy Male Voice Choir (Adelaide). Opening the wallet, I look at these physical pictures and can see and hear sounds and people from over two decades ago. There is a disc of their music here, too, which I am playing now.

Some twenty years ago I was transported home by the voices of men. It was the first time I had possibly understood the true breadth of homesickness. Months earlier, I had been made aware of the famous Treorchy Male Voice Choir touring Australia (for the first time since 1986). In the choir, I had family friends, familiar faces and my woodwork teacher, Mr (Meurig) Hughes – and it was he who had first told me of the choir’s intention to tour. And so dates were confirmed: the choristers would perform twenty-four concerts within a month moving through locations predominately on the eastern side of the sunburn continent: singing in New South Wales, Queensland, Victoria before concluding in South Australia. This final leg of their tour is were I decided to meet them. A long weekend in Adelaide. I was forwarded a copy of their itinerary and was able to plot dates, book flights and secure accommodation in the city of Churches.

And so, near the conclusion of their Australian tour, I crossed the Nullarbor Plain to fly three hours or so into Adelaide. It was my first time into South Australia. The city centre was a grid of navigable right angled streets, divided in half by a long, straight avenue called King William Street. Sandwiching these interlocking inner-city roads were North Terrace and South Terrace. As luck would have it, the choir was on the South and I the North. On arrival to the capital, I took a taxi from the domestic airport to my hotel, checked in and then walked down to the Chifley Hotel where I had been told the choir were staying. It was now late afternoon. There were two big buses, or coaches, parked opposite the hotel advertising their tour. Outside a few choristers in uniform blue polo shirts were smoking. Their accents told me I was were I was needed to be. Inside the hotel lobby there were lots more blue polo shirts – their official tour shirt when not dressed in black tie for performances. The choir had spent the day travelling from Mount Gambier in the morning, to sing in front of National TV cameras on Parliament Square promoting the tour, to then check in briefly at the hotel before preparing to go to the Festival Theatre to sing. It sounded an arduous schedule. In the hour or so that I was in the Chifley Hotel I managed to find a family friend, Clive Taylor, who told everyone – particularly designated officials – that I was his nephew. This half-truth became my passport to going everywhere with the choir during the weekend in Adelaide.

Later that night, I sat with some two-thousand people in the Adelaide Festival Theatre. It was the first time I had seen or heard the Treorchy Male Voice Choir sing as an adult. These were men I had known all my life, some there from childhood, up on stage in front of us all. After the applause of their entrance, after the muffled hush of taking places, after the first sound of melody from their voices, I was transported elsewhere. They sang songs in Italian, English, Xhosa Zulu and Welsh. They sang songs I had grown up with and grown accustomed to. There were songs sung that I knew the names of, there were some songs sung whereby I only knew the sound. The power and beauty in their voices carried through the air and thumped deep upon some hidden space of the heart. There, the emotions of exile shattered in starburst. The power within their spoken words transported me back to childhood, back to a place I left before I truly understood it; with closed eyes, I could see the colours Max Boyce sung about in his ballad ‘Rhondda Grey‘ – that it was the faces of people who lived in the old mining community that coloured the world existing there. When the choir sang the spiritual hymn ‘Oh My Lord What a Morning’ an old man in a dark suit, sat in front of me, began to cry. And in that swell of emotional longing – the brooding ache of hiraeth – there was also present a deep and never-ending bond of belonging to place and time.

The performance lasted across two halves. There had been an intermission and interludes from solo performances of choristers and singers, such as the rendition of Unwaith Eto’n Nghymru Annwyl from the compere and publicity officer of the choir, Dean Powell. There was an encore at the end. After the performance, Uncle Clive smuggled me on board one of the buses back to the choir’s hotel. There, in the lobby of the Chifley Hotel, the mood with the choristers was gregarious. We drank together and I met many friends (old and now new). There was also a grand piano there and someone began to play, and the men sung. I stayed until late, very late, before the bar closed and I caught a taxi back to North Terrace. It had been a long day. Before leaving, I had been told to report back to the hotel the next morning to accompany the choir into the Barossa Valley to see them perform in an afternoon concert at Tanundra.

It was an early start the next day. There were two buses of choristers departing the city towards the north east. As to plan, I was smuggled on board one of the buses, sitting next to Uncle Clive. Most of the men were obviously tired, some hungover. The long and demanding schedule was beginning to catch up on their bodies and vocal chords. Throw in the stresses of jet-lag, an eight hour time difference, a month-long separation from families, as well as the transient nature of living in hotels, many were happy to see the long tour draw to a close. This, their final day, required them to perform twice; once at Tanundra before returning to Adelaide for a second evening at the Festival Theatre. Due to ill-health, Uncle Clive sat out the matinee performance, so we were able to sit together in the audience and watch the choristers sing. It was a much smaller audience than the previous night. But it was the first time Uncle Clive had been able to see or hear the choir since becoming a member. During their rendition of Joseph Parry’s Myfanwy, he kept saying how proud he was to belong to them, whispering aloud to himself how good the choir sounded. And they did.

On the drive back to Adelaide one of the buses broke down. No one paid any real attention to what was happening until it was announced that the soloists and elderly choristers should go back to the hotel on the other bus, while the rest of us waited on a hard shoulder. We waited for over an hour. It was a hot afternoon, in that dry heat Australia can have, and without a working engine there was no air conditioning either. Only the radio worked. There was nothing that could be done until assistance arrived. We were in the middle of nowhere. Yet no one complained. Most slept or tried to rest. The radio helped – some sung along to the music played to pass time; an impromptu accompaniment of Cat Stevens’ Moonshadow was one which remains in the memory. Eventually help arrived, the engine was fixed and we made it back to Adelaide with enough time to return to Festival Theatre before the curtain went up. The performance – the last performance of the Australian tour – went well. Sitting among the cheering crowd as the curtain came down I felt so honoured to have been adopted by the choir over the weekend, as well as in admiration for these men who had given up their time and money to sing. They had carried their songs across oceans and continents, sung from a place deep within despite being close to exhaustion. Watching them all stand, wave and bow I felt immense sense of admiration for their craft and desire to share their passion and create belonging.

There was sadness the next morning. There was sadness because I was saying goodbye to family friends (some old, some new). They were going home. Back to where I had once belonged. There was also sadness because I was leaving their familiar reality, this understanding without explanation, to journey three hours west across the Nullarbor Plain. I did not want the connection to end. Our departing flights from Adelaide were scheduled more or less at the same time – albeit from different terminals (them the International, me from the Domestic). The choir made sure I was on their bus to the airport. In fact, they had even smuggled me to an official engagement immediately after the final concert – a sit down reception with an open bar. It had been a late night, but one which I had enjoyed, creating many new friendships – sharing in that special bond that travel can easily create between strangers. With suitcases stacked up in rows outside the bus we said our goodbyes.

Looking out now at the silent cityscape tonight, the fireworks have stopped. The sound of the wind still blows through the branches of nearby trees. Tonight I am listening again to the voices of those men singing. Their music is alive here tonight. And I know, that some twenty years later, some of those voices are no longer singing. But they are singing. They are singing in concert out across the darkness of this night sky, this moonless spring night sky. The voices of those men colour the darkness from the twinkling neon lights up towards the shining Southern Cross. Across oceans and continents. Their voices are alive here tonight.

*