The captain of Air Tahiti Nui flight TN102, Auckland to Papeete, has just announced that we are approaching the International Date Line. This is the de-facto boundary existing between calendar days. In a few minutes we will cross this demarcation of time, which runs through the Pacific Ocean from the North Pole to the South Pole; as we are travelling east across it clocks must be set back one day to compensate local time. Amazing to think that this concept was first thought of nearly 700 years ago by a scholar from Damascus called Abu al-Fida, who predicted there would, one day, be travellers who could circumnavigate the globe and they would have to accumulate an extra day in their journeys. Looking out of the window from seat 38L all that can be seen is a carpet of white cloud far below. In the blink of an eye, this flight just journeyed from tomorrow back into today – and so despite having already travelled 24 hours in the effort to celebrate my 40th birthday in Tahiti, I have just arrived back into the same day from which I departed. Not sure how this act of time travelling will actually affect the rest of my life – forever transformed in age as being however many years ‘plus one day.’

Two hours to go before landing. I think back to a book I read when I was 22 and living in London; in part, it has helped fuel the inspiration for this journey to Polynesia. W. Somerset Maugham published The Moon and Sixpence in 1919 (having travelled to Tahiti five years prior to research the novel’s topic). The novel follows fictional artist, Charles Strickland, as he abandons all responsibilities in London and Paris to follow his passion into the South Pacific. Maugham’s story is based on the life of Paul Gauguin, the former Parisian stockbroker who left his job, family and Europe in 1890 to sail to Papeete to paint, carve and sculpt. The journey took sixty-three days. Gauguin was also present the night Vincent van Gogh cut off his ear in Arles 1888. As an artist Gauguin was relatively successful; on his return to Paris he sold enough paintings at an exhibition in 1894 to see him through until his final voyage back to Tahiti in 1895. From this trip he never returned to Europe, instead continued to paint in Tahiti and the Marquesas Islands until his death in 1903 (he was buried on the island of Hiva Oa).

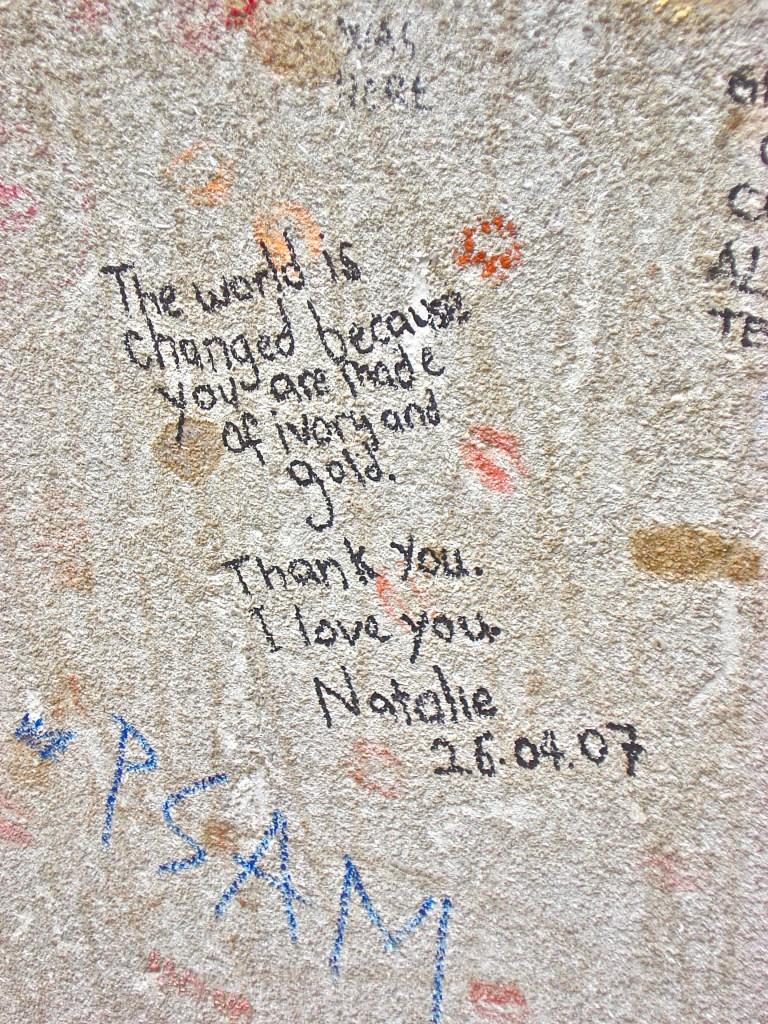

The Moon and Sixpence attempted to examine what could possess anyone to risk (and abandon) everything in the pursuit of a dream. One summation deduced is that Strickland was just one of those people who are born in the wrong place, unable to fit in with the status quo and thus has a particular wanderlust driving them on to find their peace in this life, ‘Accident has cast them amid certain surroundings but they always have a nostalgia for a home they know not… They are strangers in their birthplace and may spend their whole lives aliens among their kindred… Perhaps it is this sense of strangeness that sends people far and wide in the search for something permanent… Sometimes a person hits upon a place which they mysteriously feel they belong. Here is the home they sought, and will settle amid scenes never seen before, among people never known.’

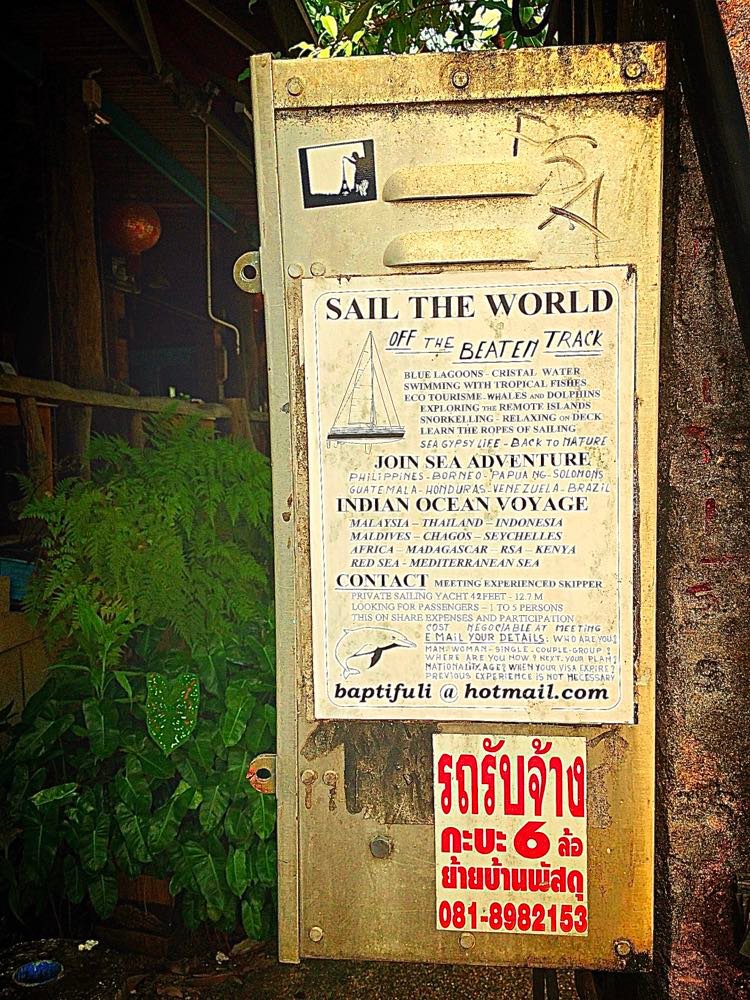

The title of Maugham’s novel also draws reference to the practical difficulty many face when wishing to pursue any dream or passion: there will always be other responsibilities which demand your attention. The challenge for all of us is laid bare by the title: the financial need to search the pavements for a sixpence while continuing to look up to the Moon for inspiration. For many, the belief and risk in pursuing dreams is one step beyond our obligation to being sensible.

Part of the fascination with those who do find the perseverance to continue on an unseen path can be due to the fact we may lack the same courage to follow a vision or passion. Yet the power within the mind’s eye to create, lead and direct us towards a particular end, outcome or goal was a trait venerated by ancient Maori and Polynesian seafarers. Without any landmarks to guide them through the open waters of the Pacific Ocean, traditional navigators would use the stars, clouds and ocean swells as beacons to map their world. Wayfinders would be trained to picture particular islands they wished to visit in their imagination. Using this ‘image’ the Wayfinder would help steer the canoe towards the specific island; as long as the image of the island was retained in the mind’s eye the vessel would find its way there.

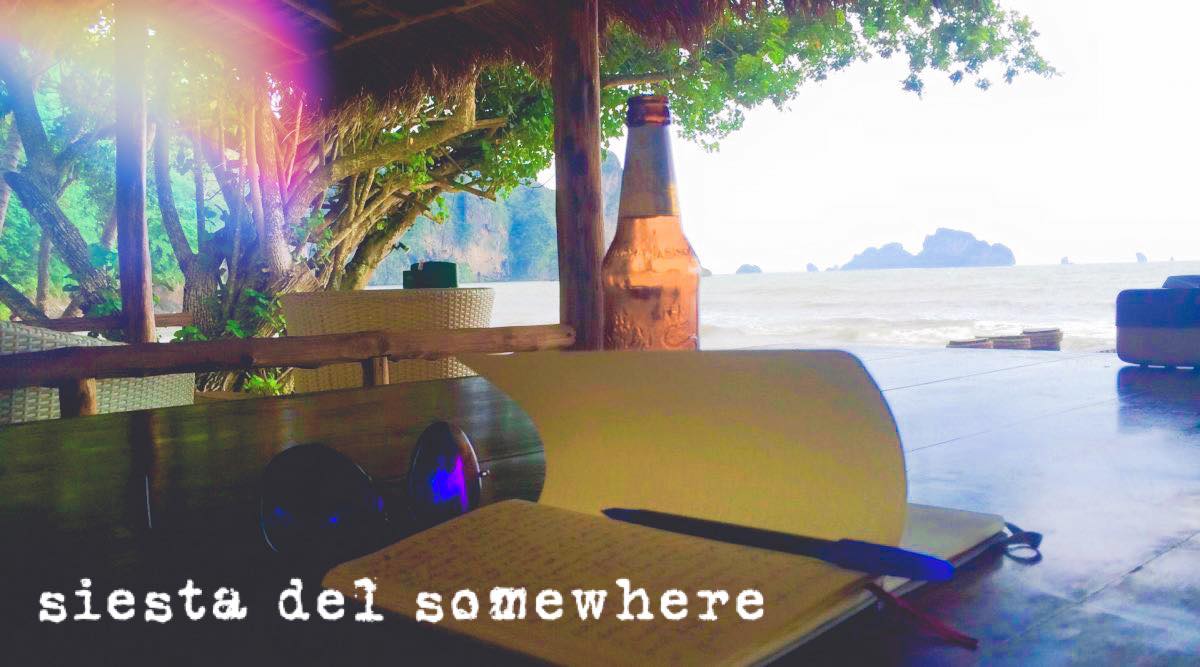

Despite the difficulty it has taken to reach here – travelling via Sydney and Auckland – I am finally in Papeete (and it is still the same date as when I left my home). All sense of time has been lost. It is dark. I feel exhausted. There is also an eighteen-hour time difference to navigate. A shuttle bus took me from Faa’a International Airport to my hotel near Mahina. I have no real recollection of the journey until we drove through Papeete – streets were dark, deserted, quiet. My tired eyes were eager to see something. It may have been close to midnight when we passed through the capital towards the Côte Est. It may have been later when I eventually checked in to hotel. Everything was asleep. Room service had ended at 10pm. I was shown to my room 3502. Split level, two floors, two balconies (one big, one small). From the smaller one connected to my bedroom, I stand outside and write here. In the darkness I know that I am facing out into the ocean, the wide Pacific Ocean. In the sky there is a huge yellow, crescent moon balancing on its back. The air is so pure. The darkness so rich. The world is full of stars and ocean. On the horizon the threat of a storm flashes and boils far out at sea, moving somewhere in a bank of white cloud beyond the black, opaque ocean. All I can hear is the sound of the Pacific Ocean. Waves coming ashore. All I can hear is the rhythmic sound of the Pacific Ocean.

Time has flown. Most of this trip has already gone in five short days. Despite the time differences I’ve managed to do most of what I wanted in this trip. It has been a long way to come for a short time (alongside the financial realities of funding this journey) – but as with most gambles in life the experience has been worth it. This was, after all, one of my dreams to come here and has now been realised. I have managed to make short trips into Papeete most days, exploring the streets, the waterfront and the Marché Municipal. Have taken a few excursions and day trips – visiting the Te Faaiti Rainforest and Mount Urufa one day; visiting the Grotte de Vaipoiriri, the Hitiaa Cascades and the Arahoho Blowhole on another. There was also a trip to the Gauguin Museum in Papeari. There was a visit to Matavia Bay and Pointe Venus where Captain Cook unsuccessfully attempted to observe the transit of Venus across the face of the Sun in 1769 (there would not be another until 1874).

Tomorrow I will be turning 40 and have organised a trip to visit the neighbouring island of Mo’orea. Supposedly, this is midlife – the halfway point of this great adventure, and if I am fortunate – very fortunate – then I get to spend the same allocation of time all over again. In Roman mythology the Fates were three goddesses who apportioned an allocation of time for our lives; whatever they decide now is fine with me, but I wonder if they factor in that ‘plus one day’ accrued across the International Date Line. Until then, let’s keep realising dreams, or at least reaching for them and the Moon as long as there’s a sixpence present to make it happen.

Breathless. Still. Tahitian sunset. My eyes are staring into yellow colours on Lafayette Beach. Yellow sun, yellow sky. Some parts should be amber or orange, but the colours are lighter than any sunset I’ve seen before – spectrums of brilliant yellow, gold, sunlight shining through champagne. It is late afternoon. Endless flat ocean, stretching far forever into these Pacific skies. Waves are crashing ashore. White foam churns on black sand, turning pink in this equatorial light releasing a burst of rainbows in the spray thrown onto the shore. Pebbles rattle as the retreating tide inhales another breath before the next crash. Some children play in the surf beyond the breakers. A fisherman loads up his bait on the reef to my left and casts out into the water. The sun has lost its glare, heat and sting for the day; its warmth is across my skin. The ocean continues to crash along the shoreline and the sand is constantly changing colour. It seems to flicker with flecks of gold within its black, volcanic ash. It is fine like a powder; when wet it shimmers like silk. As the ebbing waters recede pack into the Pacific the wet, black shoreline seems to shine a dark blue, leaving it coated there. It is extraordinary. The whole beach is an alchemy of colour. Even now, looking at the ocean, some parts of it seem to be green (a dark emerald), with half of it blue, with bands of gold and turquoise near the reef. The colours are constantly changing. Some parts blue, some lighter, some bits black, some bits of bottle-green, the patches of pink still swirl in the surf (in the shallows). The sun is setting so quickly. I had heard about the way the sun drops quicker at the equator at a day’s end; it is racing down quicker than the colours of sunset can follow. I watch the yellow disc meet the edge of the horizon. Some French teenagers sit further up on the sand behind me, one has a guitar and all begin to sing Bob Dylan’s ‘Knocking on Heaven’s Door.’ Their singing fills the air. The ocean keeps changing colour. The waves of the Pacific Ocean keep coming ashore.

Tahiti is everything I imagined it to be.

*