The day had been spent writing. It was important to find a routine that worked; for good writing it was necessary to find a rhythm (or to let the rhythm reveal itself to you) – something, in the words of the Poets, which enabled you to hear the Muses sing as clearly as possible. When you committed to creating momentum, and worked patiently within in, then the words just flowed and the magic happened in front of your eyes. Waiting for inspiration is as pernicious as blocks, procrastination or the fear of a blank page. Much has been said about how to write, when to write, how often to write. In the end what works for you is probably best: but you have to find your own rhythm. For some, the most potent time is around dawn – brahma muhurta – when creativity literally comes down to meet you; for others the alchemy is best experienced after dusk, as documented in the verses of Dylan Thomas:

In my craft or sullen art

Exercised in the still night

When only the moon rages

And the lovers lie abed

With all their griefs in their arms,

I labour by singing light.

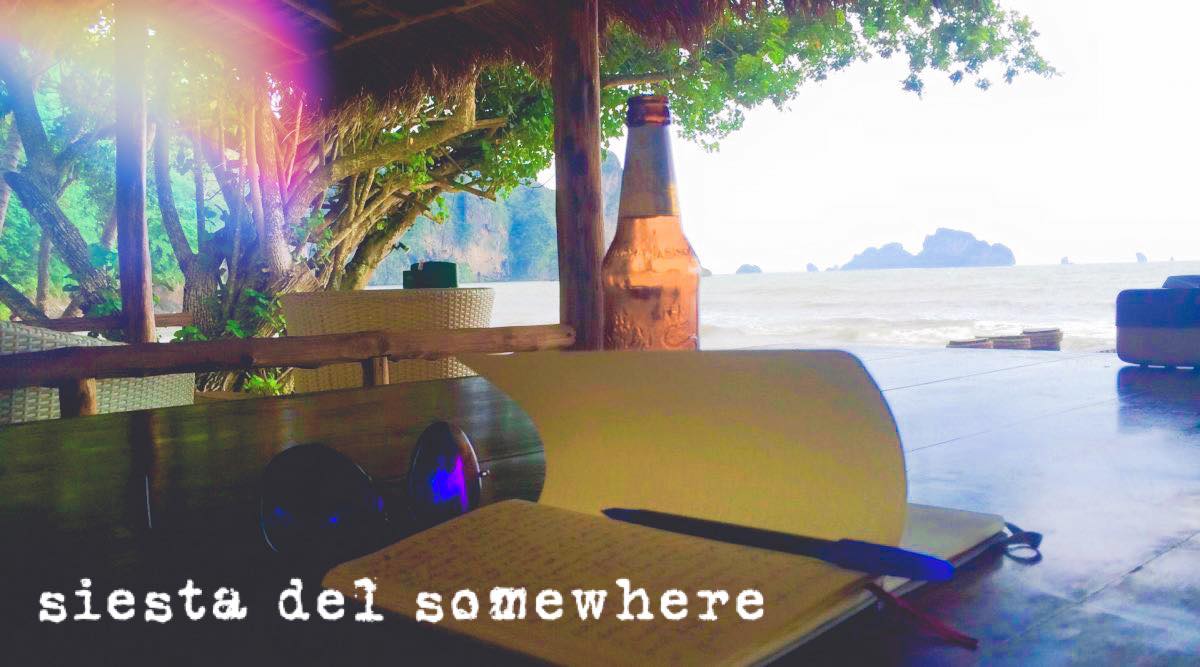

For almost a month I had found a routine that really worked for me: a walk along Tuban Beach before breakfast; to write for several hours at a desk in a room I had rented until lunch; a couple of afternoon hours editing sitting outside; finishing with a walk near the ocean at the day’s end – leaving the nights free. Long mornings were spent sat at a desk overlooking a garden with green, flat tropical leaves, which moved and swayed in what little breeze dared whisper. After lunch, I moved onto a balcony, a bar or cafe, editing what had been written the day before – all the while watching the afternoon skies grow heavy and then burst with rain. The flat palm leaves were drummed into a kind of submission by the downpour of raindrops – the surrounding greenery seemed to become more vibrant in sound and colour because of the rain. This routine had worked, the project I was working on was almost complete.

Walking along the beach at late afternoon (before the sunset) helped rejuvenate and untangle the mind from words and ideas. It was a good way to avoid burnout on any long project. The beach was not far from my room – a short walk through several narrow streets (jalan or gang). Roughly, I would arrive there at that time of day when shadows had begun to fall through the trees and stretch themselves out across the shoreline where wet, tropical tarmac gave way to the sand. The strength of the sun had long begun to fade. Mosquitos were beginning to make themselves known, nipping and biting. The day itself felt tired in some way.

Some days I would walk there as the tide crept its way back up the beach. The incoming waves growing in noise from a still and silent ocean. Local children would play in the foaming surf; tourists taking photos of the flat silver ocean beyond them, waiting for the pink sun to set and burn Titian colours across the sky. Planes flew upwards from Ngurah Rai Airport, passing the beach, reaching up overhead journeying home. Sometimes patches of yellow light broke from above the clouds and over towards the north, the mists would clear and Mount Batukaru drifted into view.

At that time of day, many of the sellers would be packing up – taking home what had not been sold to try again tomorrow. The odd tourist would walk past but the last sale of the day had possibly come and gone. Heads low. Some of these sellers worked on the beach the whole day. Time to count up the rupiah and see what has been made for the family today. Not much left to say. No more customers will come now. Through the familiarity of routine I got to know some of these faces. Andrew sells necklaces. He wears a yellow hat with his name on it. He has four children, three boys and one girl. He tries to sell me a temporary tattoo. OK don’t forget me tomorrow – remember my name. Eric is selling a crossbow. He also has a blow-dart for sale. Eric speaks Italian. He learnt it on the beach. He speaks fluent Italian. A friend bought him a book. Each day he learns a little more. Step by step. Eric also speaks Javenese, Balinese, Indonesian, English, Spanish, French and a little German. He learnt it all on the beach – a la spiaggia. Most of the sellers here have their own patch. Some sit under frangipani trees during the heat of the day. They sell for good price, cheap price, welcome to Bali price. A blond tourist has three Balinese women braiding her hair on the beach outside her hotel. They say all the right things to her: she is pretty, she smells nice, she has beautiful hair. They ask if she is Australian, or American, or English. They each repeat their names if she needs anything else – You want to buy a hat tomorrow? You come to Jenni. Kiki, Lisa, Jenni – all three braid her hair.

Yayan Nuken sees me and comes and tells me his name. He writes it in the sand so I can see it. ‘YAYAN NUKEN.’ He gets me to pronounce it. He sells wooden statues of the Buddah. He sells the most beautiful shells in the world (laid out on the sand in three, neat rows). He says, I make nothing for one week. I pray to make a little more money for next week. The rain keeps the tourists away. No tourist, no money. You want a tattoo, Boss?

Further along the beach, the Lupa floats about without care on the flat silver ocean. It is visible from a distance, being a distinctive bright pink. Lupa is a boat – a jukung – a long, hollowed wooden outrigger with long, lateral supports. It is anchored in waist-deep water and having spun and drifted all day it now bobs and nods on the easy sea. Clouds move east filling the Balinese sky with moisture and heat. Captain Nyoman stands looking out to sea. No tourists. No good. No money. Arms folded over his chest he walks along the water’s edge. He sees something, bends down to pick it up. He looks at it in his hand, then tosses it out for the ocean to keep.

Some days it was nice to walk the full length of the beach – to go right down to a perimeter fence that segregated something from the rest of us. One of the first times I ventured that far, I saw a lone black silhouette standing in waist-deep water ahead of me. By the time I reached him, he was standing up behind a stone breakwater facing the ocean, holding a thin fishing rod with the line sunk under the water. As I got closer I could see he was a young man, maybe in his twenties, hidden underneath a navy blue polythene poncho. He wore a baseball cap. On seeing my approach, he nodded and said, ‘Look for the stones to stand on.’ I looked down and there in the sand was a hopscotch smattering of octangular shaped stones sunk in the water, big enough for feet to walk on.

I joined the fisherman on standing on the breakwater. Elevated up, he water stood around our knees with the breakwater at our chest.

‘Have you caught anything?’ I asked.

‘No, not yet. I try to catch something.’

‘You work on the beach?’ I asked.

‘Yes. Every day I work here, I sell ice-cream for the tourist.’

‘You are from Bali?’

‘No, I am from Java. But now I work in Bali.’

‘Do you have family here?’

‘Only my brother,’ he pointed to a smiling figure standing behind us up on the shore.

They both wore the same plastic ponchos.

The soft waves of the pushing ocean rolled around the front of the breakwater, bouncing back into the face of the Indian Ocean before being washed up on shore. The brother pointed out to sea and shouted something to his brother. I turned, but the fisherman already knew what the brother meant; his line was taut. He caught something on his line. He clicked his reel and began to play with the fish. His line bent, with the nose of the rod dipping down into the water, pulled harder before flexing and relaxing and flexing again. The brother said something, wading in the water, across the octagonal stones and up onto the concrete ledge behind the breakwater. All the while, the fisherman kept focused, holding the rod with his left hand, spinning the reel with his right. His bare arms poked out of the poncho, with veins working hard beneath his skin. The rod kept being pulled beneath the waters, engaged in a frenzy of tight, spasmodic combat. The fisherman reeled and began to pull the fish in from the deep.

Crack!

And then the line snapped. It just broke.

The three of us stood there for what seemed a moment in time. I heard that sound that falling rain makes when it hits the ocean’s surface to create pockmarked rings. The fisherman stood holding what was left of his rod and turned half smiling in a kind of apology for something.

‘It’s gone,’ he said to me.

The brother turned and jumped into the sea, wading back to shore, head bowed.

‘That was going to be our dinner,’ the fisherman said.

Instinctively my hand slapped the pocket to my shorts for some kind of recompense. But it was empty. There was nothing there to give. The fisherman smiled, and jumped down into the sea. I stood still on the ledge for a moment, looking out at sea, listening to the rain.

The two brothers stood at the edge of the shore waiting for me to join them.

‘Where do you go now?’ I asked them.

‘Home,’ they replied.

I shake their hands. ‘I’m sorry about your fish.’

‘Don’t worry God will look after us,’ said the fisherman.

‘I wish I had something to give you.’

‘Don’t worry. Wassalam Mualaikum.’

And then we parted.

Each night, my body would feel better for the walk and my mind would be at rest (free from thoughts and ideas for another day). Back in my room I could often hear the evening rains falling on Tuban Beach. It was a time of day many gave thanks. It was a time to give thanks to the gods who protected them, and for the good luck and for the day that just happened. It was a time to say thank you for what prosperity had run through your hands. It was a time to express gratitude for family, for the love to which we belong, and for what roof spans above our heads this night. It was a time for offerings, to ask for the chance to try again tomorrow. To hope for a better day tomorrow. Terima kasih. The rain fell often on Tuban Beach.

*