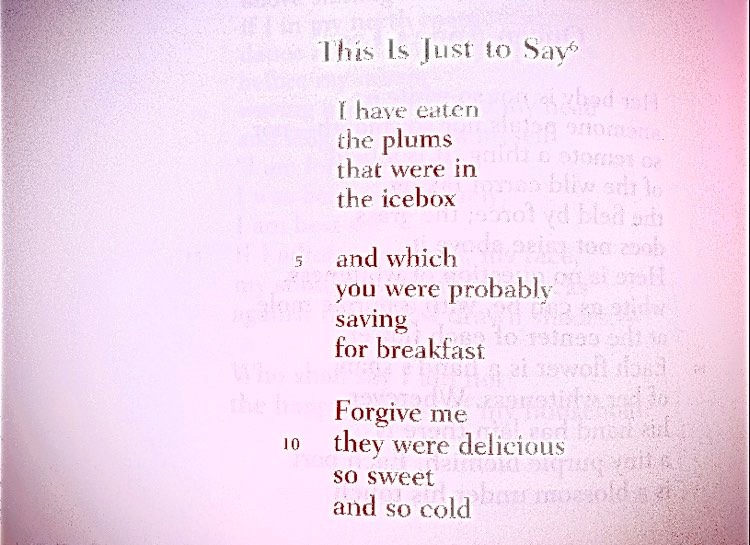

In Thai language the word for dog is หมา and when pronounced it sounds like ‘ma.’ Often the a sound is long and held a little before ending with a rising tone.

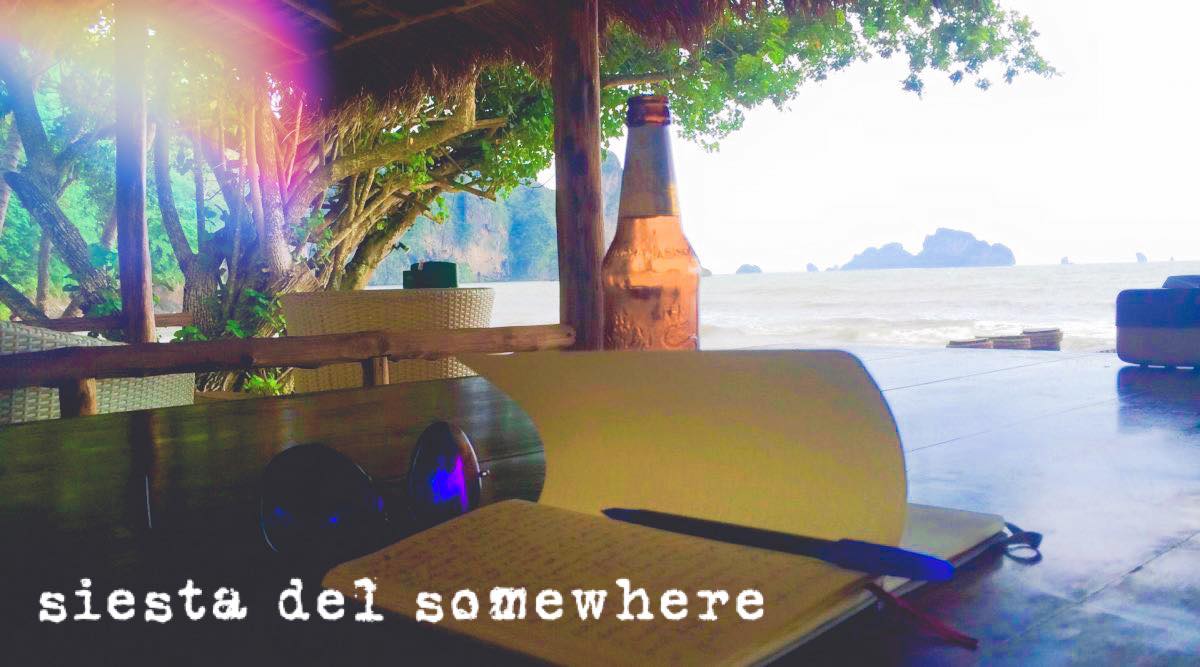

Towards the far end of AoNang beach – near the little shrine at the foot of the Monkey Trail – there were yoga classes held each day at sunrise and sunset. Having booked in for a morning class, I had arrived early and so waited near where I had seen the class advertised. I leant against a small wall facing the beach. While it had been raining when I first woke, the morning was overcast with rolling clouds, grey and thick, curdling low above the ocean. This was low season – or rainy season – when downpours and electrical storms were more frequent. Despite this, it remained warm and humid. Many relaxing afternoons had been spent under cover watching the rain and listening to it fall in AoNang.

It had taken me ten minutes to walk to that spot from my hotel along the shoreline. The beach was quiet. A few tourists were walking on the sand. There were about three or four elderly women crouched close to the ground digging for shellfish in the wet sand. They each wore pink headscarves as coverings, and collected whatever they found into small, plastic buckets. Their hunched bodies moved in silence across the shoreline. Behind them, an imposing ridge of limestone rock towered above the trees and hotels reaching out into the Andaman Sea – cutting off that end of AoNang from the neighbouring beaches of Railay and AoNam Mao.

A continuous warm breeze blew in offshore carrying the sounds of long tail boats labouring against the receding waves. In the shallows, a fisherman waded out waist deep into the Andaman Sea with bundles of red nets in his arms. I couldn’t tell if he was laying the nets or unravelling them in the water. The waves were breaking all around him, moving so fast, full of sound. Out on the horizon there were three or four islands, their outlines fixed and unmoveable. Koh Poda, the largest of them, was directly in front of me.

A gust of wind made the wooden wind chimes hanging behind me rattle and echo. They belonged to the restaurant whose wall I was leaning up against: Plaifa. Its signs and menus sleep stacked up on the empty counter and closed kitchen (they opened for breakfast later in the morning). Plaifa had lots of aloe vera growing in short, fat pots outside an area between its service area and the next restaurant. Birds the size of matchboxes chirped and hopped about the pockmarked sand and fallen frangipani flowers there. Light struggled through the flat, broad leaves of the trees surrounding the restaurant. Dappled patches of shade moved on the ground as the wind blew in off the ocean. The scent of jasmine incense being burnt was present in the air for a brevity in time before the humidity and rolling waves overtook the senses.

Looking out all around me the two dominating colours were grey and green. Overcast grey, tropical green.

The sound of a motorbike revved out of the silence. The bike travelled along a side road, and cut across a small stone bridge across a river, and parked at the side of Plaifa. A woman with long black hair tied behind her head, got off the bike which was fashioned with an open, roofed side carriage (like a tuk tuk). There it had carried a basket of towels and several black yoga mats rolled up together. This was to be the yoga instructor. Moving fast, she placed the basket and mats on the ground, beneath a tree, before making a couple of trips to carry all onto the beach. In no time she had done this and planted a tall, red flag nearby advertising her yoga class.

I moved down from the small wall to introduce myself to the instructor. She wore a red singlet and blue leggings and by the time I reached her, she was already setting up the mats on the beach. I offered if I could help her set up.

No need, she said, all ok.

The instructor rolled out four grass mats onto the sand, before placing a similar number of smaller, yoga mats on top. On top of each was placed a red hand towel with a bottle of water. There would be three others doing the class with me.

As the instructor set up her own mat – directly facing us with her back to the ocean – a girl walked along the beach to join the class. She introduced herself – she was travelling around Thailand and had come from China. As we all began chatting, a couple walked along the front of the restaurants (where I had just been) and dropped down on the sand. They were two Londoners repeating the class and knew the instructor – having first arrived in Krabi a few weeks earlier before spending some time over in Koh Samui and had now returned.

As we were now all present, the class could begin.

We were invited to sit down on a yoga mat. The instructor formally introduced herself and provided some information about herself, where in Thailand she was from, her own personal journey with yoga and what we would be doing in the class: some breathing exercises; stretches, twists and balancing poses (asanas); and, finish with a shavasana (or meditation). We all sat on our mats facing the instructor and the ocean. We were told to close our eyes.

Our first practice was something called Nadi Shodhana. It was a practice of being seated and breathing in through one nostril and breathing out through the other. It was a practice used to still the mind and body, in preparation for yoga. We were each guided and shown how to do this: to rest our left hand on our knees and using our right hand to alternate the index finger and thumb in closing off our nostrils as we breathed. We brought our hands up and closed our left nostril and inhaled deeply and slowly through our right nostril. The instructor counted to four. We then pinched both nostrils closed and held our breath as the instructor counted again. Then we were told to release the left nostril and to breathe out slowly to a count of six. The practice then switched sides; we breathed in through our left nostril, pinched closed both nostrils and held our breath, before exhaling through our right.

We practised this breathing technique several times. During the practice we were told it was a method to help calm the mind and calm the nervous system. In the thick humidity of the beach I laboured with this and felt my lungs begin to burn. Holding my breath was proving so difficult. Beads of sweat became more prominent on my skin. I felt sweat run down my forehead. I could hear my heart beating hard within my body, sounding with exaggerated thumps in my hearing. I kept my eyes closed and tried hard to follow the instructor’s count to breathe but I struggled and found myself needing to gasp and sip at the air. I couldn’t tell if it was my inexperience with the technique or the heat and humidity of being outside on the beach. Even though there was no sunshine that morning, the humidity had a presence and it felt as though it was building.

The practice was then cut short. I felt a sudden thump in my ribs and torso at the same time I heard a scream. Eyes open I saw myself as part of a tangle of limbs: the Chinese girl had crashed into me, lunging away from a wild dog that had encroached on her mat and now lay down on the sand.

It’s ok, it’s ok, said the instructor. This dog always comes here. He likes to join in meditation. He’s a good dog, not nasty, never bites, but always causing trouble.

The dog belonged to a group of dogs that seemed to live on the beach, never charging or bothering people; sometimes they barked. The dog seemed placid and at ease. If I had to guess, it looked like a small Labrador with thickish fur. It had a mixture of gold and black fur (its back, face and ears were black while its belly and legs were gold). Uninterested in us, the dog rested its gaze up the length of the beach laying on its stomach with its elbows bent – almost in a Sphinx pose.

The instructor told us not to worry about the dog. Just let him lay down, ignore him and he soon will go. He is a good dog. Has a good heart: ‘jai dee.’ She then told us in Thai language the word for dog was ‘ma.’

Trusting the instructor, we went back to our breathing exercises. When we had finished and opened our eyes again we noticed that the dog had gone. None of us had heard him leave (a trail of paw prints in the sand suggested that he had headed back up the beach).

With this aspect of the class complete, the instructor took us through the rest of the practice. This was the most challenging and demanding sequence. We did all sorts of poses and balances (seated and standing) such as the warrior and triangle poses. There were lots of twists – holding our bodies still as we tried to breathe space into any physical limitations we had on that morning.

During one pose I looked out at the ocean. My perception of everything felt slower. The sea was changing colour before my eyes. Greens, blues and a kind of luminous shade of jade. Clouds had continued to build – as had the humidity. I felt drops of rain begin to fall on me. A sheet of cobalt blur drifted across the ocean. At first this seemed to be moving across the horizon, almost parallel to the shore, then one by one the islands in front of us began to fade. At first, they became outlines, then disappeared behind a curtain of mist. The more the wind gathered, I could begin to see the long, thin shadows of rain falling. This was a downpour moving towards the shore. Some tourists stood in the shallows of the ocean, all photographing the changing colours. A small child and a grandfather were walking nearby holding hands when suddenly the child broke free and ran to the ocean. There he had found something and held it aloft in his hand. He showed it to his grandfather and ran back to the ocean – skipping occasionally – before throwing whatever it was back into the rolling surf.

Then a sudden gust of wind hit us like a wall of noise. The winds sounded loud and howled. Thunder rumbled somewhere in the distance. There was no horizon only grey. The instructor abandoned the class for a moment. We all ran, taking cover beneath the trees and bushes near Plaifa. Safe, we stopped – laughing, panting, listening to the downpour of rain on palm leaves over our heads. We saw the gang of stray dogs running further up the beach, seeking shelter near some massage huts towards the hotels.

And so, the rain fell. And it kept falling. At first the noise was deafening. The surface of the ocean danced and vibrated with concentric circles of rain – patterns appearing everywhere all at once then gone in an instant. The downpour muffled all other noises. The world for that moment sounded and felt so different. Visibility changed. The large limestone rocks at the end of the beach were obscured – just shades of green and grey. At my feet, small puddles of water formed in the wet sand. The small birds I’d seen hopping about earlier now hid in the upper branches, finding pockets of sanctuary, and struggled to balance as the wind continued to blow in gusts.

Then eventually, rain began to ease off before resting at a steady drizzle. Thunder continued to sound but was far away. The instructor gave us option of going to the yoga studio up in the town to continue the class there. But we were all happy to finish the remainder of the class under the trees and foliage we had camped beneath. We were already wet and there wasn’t long left of the practice. And so, this is what we did.

We continued with our class in a final flow of poses and balances. It felt so nice to be standing still and so fully present as the sound of rain tapped the banana palms and frangipani trees around us. The green of the limestone ridge and its trees seemed to come alive with a vibrancy I’d not appreciated before. Everything shone with a sheen and glossiness. I looked above me. At the trees. One trunk was covered in vine weepers, which curled and wrapped itself around the main stem before moving off onto other branches. Some branches were thicker than some of the tree trunks around us. Another gust of wind moved them in unison. Raindrops fell in concert landing on us and the wet sand. Many leaves managed to hold on the raindrops which seemed to sparkle with life as the light shone through them as the swayed on the moving leaves. The wind blew cooler air across the sea, dispersing the humidity. A large black and white butterfly flew between the raindrops, across my sight of vision until it disappeared into the dark green leaves.

I managed to look out again at the ocean. The whole body of water seemed calmer now, the waves moving as a single moving force breathing in and breathing out, collapsing as small waves onto the shallows at the shoreline.

As the class neared its end, the instructor asked us to stand motionless and to close our eyes. We were asked to just observe what we felt within and to be a witness to that.

I can remember closing my eyes. Standing there without thought. Just breathing in the warm, dense air. I can remember feeling the oxygen moving through my body and we began moving our arms over our heads, then in a circular motion down towards the sand, then back up towards the sky. We did this several times. Breathing. Eyes closed. Listening to the ocean. Listening to the rain falling on flat leaves. Everything felt centred. I could hear the waves of the ocean roaring towards shore. I could feel how wet my clothes were against my skin. I felt the warmth of the sea breeze continuing to blow. I felt contentment. I needed nothing. We kept moving our arms in circles. My body felt lighter, alive in movement, liberated by the breath moving within it. We were told to inhale and exhale in sync as we moved our bodies.

Then we were told to stop. And to just stand still. Keep your eyes closed. Everything was black. I could hear the ocean. I could hear the wind. I knew I was standing on the beach but it was as if I was no longer within the body. There was no sensation of floating. There was no sensation of euphoria. It just felt as if I belonged to that moment in time. An intense belonging and harmony. As if I was a part of time and space (no longer a separate entity). There was energy within everything on that beach; the wind, the rain, the ocean, the sounds, the sand, all the people around me, all the animals on the beach – we all were united in that moment and belonged. And that belonging was its own sacred energy – alive in me, moving through all.

Belonging. No separateness. Oneness.

When I opened my eyes, I watched a wave come out of the depths of the ocean. I watched it rise up then crash onto the shore. It fell face first onto the wet sand. It became stillness. Then it seemed to move backwards, scooped up and dragged back by the tide of the sea. I watched it change into a new wave, rising above an oncoming swell before it disappeared back into the depths once again. Belonging. No separateness. Oneness.

Finally, the instructor prepared us for shavasana. We returned to sitting on our mats and were again instructed to close our eyes. We were guided through a set of breathing exercises. Filling our lungs with air. Asked to hold our breath. Then allowed to breath out through our mouth. This was repeated several times until we were told to return to allowing our own bodies to breathe. With eyes closed we sat in silence. I felt a feeling of contentment again. Of peace and happiness and belonging. Then, keeping the eyes closed, we were told to rub our palms together to create heat. To keep rubbing and then place our palms over our eyes, then onto our shoulders. We were told to: send good energy out into the world – to our family, to our friends, to our parents, to our siblings, to all animals, to all beings, to ourselves.

Then the instructor sang Aum. It rose from within her. The sound resonated and reverberated. I had heard singing bowls do the same with a rising vibration – but the instructor was doing this with her voice. I could feel the vibration of sound moving through my body, through my chest. She sang this Aum three times. Each time as powerful as the first. Then when she had finished, we remained in silence before she asked us to gently open our eyes.

Waves were rolling ashore from the ocean. The sky was still overcast with clouds making the colours of the ocean jade in colour. At the end of the beach, the ridge of limestone rocks remained standing in the waters of the Andaman Sea. Longtail boats continued to streak across the ocean moving towards Railay Beach and AoNam Mao Pier. Chunks of cumulus cloud drifted along the horizon. Raindrops hung from branches like jewels.

And there laying on the beach, the dog had returned to the class (in meditation)

*

Yoga Balance AoNang:

web: https://www.yogabalancethailand.com/

contact:yogabalancethailand@gmail.com

Classes: AoNang Beach (Mon-Sun)

Morning Class 7:30 am – 9:00 am

Evening Class 5:15 pm – 6:45 pm