PART ONE: MOONLESS NIGHT… STARLESS AND BIBLE BLACK

And so begins the long jet lag into darkness. Woke about an hour ago. Still only 2am local time. Wide awake. Everything silent. Everything dark. Everything Christmas. Blurred memories of the past twenty four hours – from airport to here – are distilled. Day began early long ago. Bit of a headache as I entered the airport. Did the check-in. Made my way through customs and immigration. Lots of people about. Felt hungry. Huge queues, overpriced food. Went and waited by my gate for the flight to board. Called in zones. Boarded. Had an aisle seat. Flight full. Quiet. Can’t recall watching much (if anything), just slept. Felt so tired. Looked at upgrade offers. Managed to sleep ok. Changed flights hours later. Half way home. Transit. Airport big so big. Airport easy to navigate. Escalators. Security checks. Walked through Duty Free (last minute Christmas gifts). Made my way over to gate E4. Lounge organised in zones ready to board. Guy sat nearby coughing, coughing, coughing.

Flight home called on time. No delays. Had a window seat. Girl sat next to me and slept most of way. Guy sat next to her and kept his bobble hat on for entire flat. Awake for most of the flight (wish I’d brought a book to read). Runway lit up in darkness as we took off. Could see the lights on buoys and boats floating in the sea.

Flight soon passed. Time went fast. Flew over names of countries. Some parts seemed to take longer than others. Eventually landed. Home. Croeso i Cymru. Familiarity of the airport. Two languages side by side. Nadolig Llawen. Immigration stamped my passport. Home. Red Dragon visible everywhere. Y Ddraig Goch. Words of Dylan Thomas sound in the air:

To begin at the beginning:

It is spring, moonless night in the small town, starless and bible-black, the cobblestones silent and the hunched, courters’-and-rabbits’ wood limping invisible down to the sloeblack, slow, black, crowblack fishingboat-bobbing sea.

Familiar faces waiting to greet me. Familiar car. Familiar drive home. Familiar shapes and shadows of landscape. Arriving home for Christmas. Outlines of mountains against the night sky – frozen stars cast out across the endless black. Christmas lights shine in the Rhondda darkness below. Orange lights in homes and pubs, people talking, people coming and people going. Radio songs. Dreaming of whisky and open fires. Driving home. Familiar sights. Across the Bwlch mountain road, the lights of Cwmparc down below, the lights of Penrhys on the mountain across the valley, Cwm Saerbren with its back turned facing out instead towards Treherbert, temperatures close to zero. And then roads home that I know with my eyes closed. Body and eyes heavy. Home. Eat around a table. Talk and conversation. Body and eyes heavy. Crashing through the stars and the singing, hymning dreams. Home again. And then sleep.

Wide awake. And so I decided to get up. Crept around the sleeping house. Showered. Ate breakfast. Coffee on the stove. The slow wait. Watching the silence of the blue gas flame dance around the metallic stovetop coffee pot. Waiting. Looking out into the darkness beyond the windows. Nothing else but the darkness of night. Endless night. Silent Night. Christmas Night. The coffee pot gurgles, hisses and steams through the silence. Golden brown aroma fills the chill of the winter kitchen. Slowly pour the coffee into a patterned cup. Steam rises into the dark moving slowly like the Star of Bethlehem. The house is still; the house is silent. The whole world is asleep.

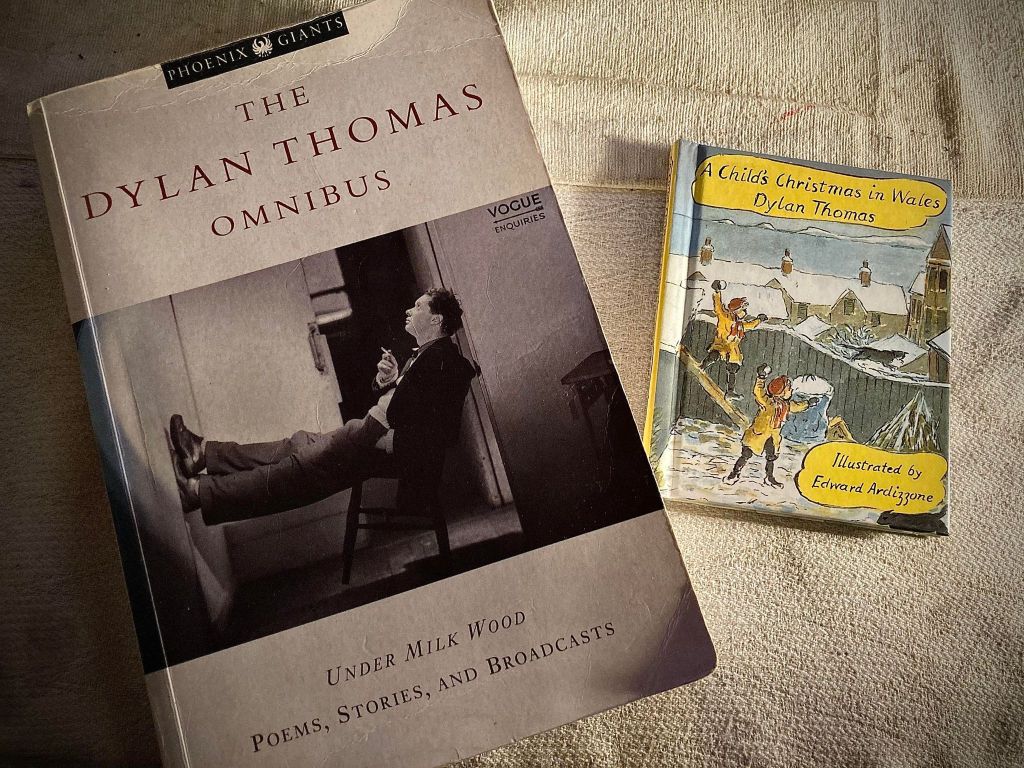

Here at the kitchen table, this table which has seen so many family dinners, Christmas dinners, birthdays, sadness and all the joys you can hope to imagine; here at this kitchen table there exists a stillness which is known only within this family home. And so, with a lighted fire heating the air, coloured lights casting Christmas shadows far and bright, I sit and drink my coffee. It will be hours before daylight comes. There is a book on this table – Dylan Thomas. And so, in this stillness, I sit and drink and read.

PART TWO: A CHILD’S CHRISTMAS IN WALES

The poet Dylan Marlais Thomas was born in Wales in 1914. An output cut short but ultimately prolific and fulfilled – words and verses sung across the rooftops in a brevity of colour, alive in moonlight, carried across the ages, spoken still, captured in celluloid, dancing in the waves along coastal shores and the deeper waters. There were poems. There was a play. There were short stories, too. Despite having Welsh-speaking parents, Thomas wrote only in English (his was a generation of people who had been discouraged from speaking the Celtic language of their parents and so were eventually passed down as ‘Anglo-Welsh’ writers). Despite this, the richness of sounds alive in the Welsh language – and its poetry, such as the chimed consonants which sound within verse known as cynghanedd – finds itself present in much of the prose and craft of Thomas. This mesmerical use of vocabulary (once described as a wrongness sounding right), plays a creative reinvention of the English dialect and conveys the sounds of an older language through it and on to a non-Welsh speaking audience.

Dylan Thomas wrote ‘A Child’s Christmas in Wales’ in 1945. The story draws on a flashback of an imagined childhood of the poet, borrowing from nostalgic memories of Christmas and his upbringing in South Wales. The story also highlights the way that Christmas can draw us home – physically or in our imaginations and memories; how it remains a tangible link to the embers of childhood and the blur of memories collected there from a time we can no longer access.

It belongs to his collection of short stories, although originally appeared as a BBC radio broadcast a couple of years earlier; its title, then, ‘Reminisces of Childhood.’ As with all bodies of work, the draft keeps evolving – wants to improve – but at some stage you must let go. The myth of Icarus speaks to us of the dangers of flying ever upwards towards the Sun – the quest for high ambition. And if you hold on to a vision for too long, striving to create an unparalleled perfection, an awful realisation awaits you in that it has consumed every aspect of your life. As with all bodies of work, you must let go eventually in order for them (and you) to belong in the world. And so, amalgamating other talks, broadcasts and drafts, ‘A Child’s Christmas in Wales’ was published in Harper’s Bazaar in 1950 (before a final version was recorded commercially by RCA in New York in 1952).

It was this final version that helped establish the popularity and admiration of Thomas as a poet and a writer following his death in New York the following year.

PART THREE: SAINT STEPHEN’S DAY – GŴYL SAN STEFFAN

The sun is rising. From the vantage point of the horse-shoe bend up on the Rhigos mountain road I look down the Rhondda Valley and see the low-angled sunlight pierce through the freezing fog that clings to the landscape. Morning has broken. The sky is clear – its veil of night has now gone. A thin, crescent moon shines bright with Venus (both visible in the Eastern sky). The first light appeared at about a half-past seven. Slowly, darkness began to lift. Outside in familiar streets, frost sparkled. Coated on blades of grass, tarmacked roads, frozen stones, frost sparkles now. Everything is painted cold.

Vapour trails from passing planes catch the streaks of yellow sunshine high in the blue winter sky, turning white in amongst the Christmas reds and rose of the morning chill, and hang suspended there in the glacial heights. Everything is so quiet. My eyes move along the valley, across the shivering homes and the trees without leaves. There are allotments empty and frozen on the mountainsides. There are horses roaming there and billowing great clouds of heat into the air from their nostrils. I watch a train pull in from Cardiff; sunlight blinking in reflections against the windows as it moves along the Baglan Field towards the station and the end of the line. From here I can see all the landmarks of home: the tall, clock tower of the old Ninian-Stuart Con Club in Station Street, the giant monkey tree now standing over the Marquis of Bute Hotel, roads and streets criss crossing as they always have, smoke rising from the Nag’s Head as it sits in the lap of the majestic Cwm Saerbren basin. And then in the silence of Christmas I realise that everyone I have ever known and loved has once lived there, down there, was from there, was once there.

The holy silence is complimented by the song of the robin. It is the robin’s winter song. This sacred bird sings so clear from the woods of the Rhigos mountainside behind me, and the song carries out across the valley bringing familiarity and meaning to the cold, Christmas morning. And then the words of Dylan Thomas reappear again. There’s a wonderful line that appears in ‘A Child’s Christmas in Wales’ – right at the end – where the child narrator leaves the adventures of the December snow and the cold and returns back into the warmth of his family home: Everything was good again, and Christmas shone through all the familiar town. And here is home and everything is good, and Christmas shines on throughout all of Treherbert.

*