Opposite the ferry terminal at Quai de Vaiare, on the Route de Cienture, was a small restaurant called Maeve Pizza. There was nothing spectacular or flamboyant about it. It just happened to be there as I walked past and I took a chance on it. There had been a large red Coca-Cola advertisement board leant against a palm tree, on which was handwritten in yellow chalk: Café – Thé – Chocolat Chaud – Glace – Pizzas – Hamburgers. A small courtyard turned in off the road. Occasional tables and chairs were dotted about in pockets of sunlight. Against one wall, beneath a large hand painted frangipani flower, was a long table and bench which faced out towards the Quai. A large generic menu was on display in front of a wooden countertop. The menu, weather-beaten in the corners, displayed a long list of pizzas in French and English. Having ordered Hawaienne avec anchois, I sat down at the long table resting my back against the wall. In front of me was the empty berth waiting for the ferry back to Tahiti. It would have to arrive from its afternoon service from Papeete first.

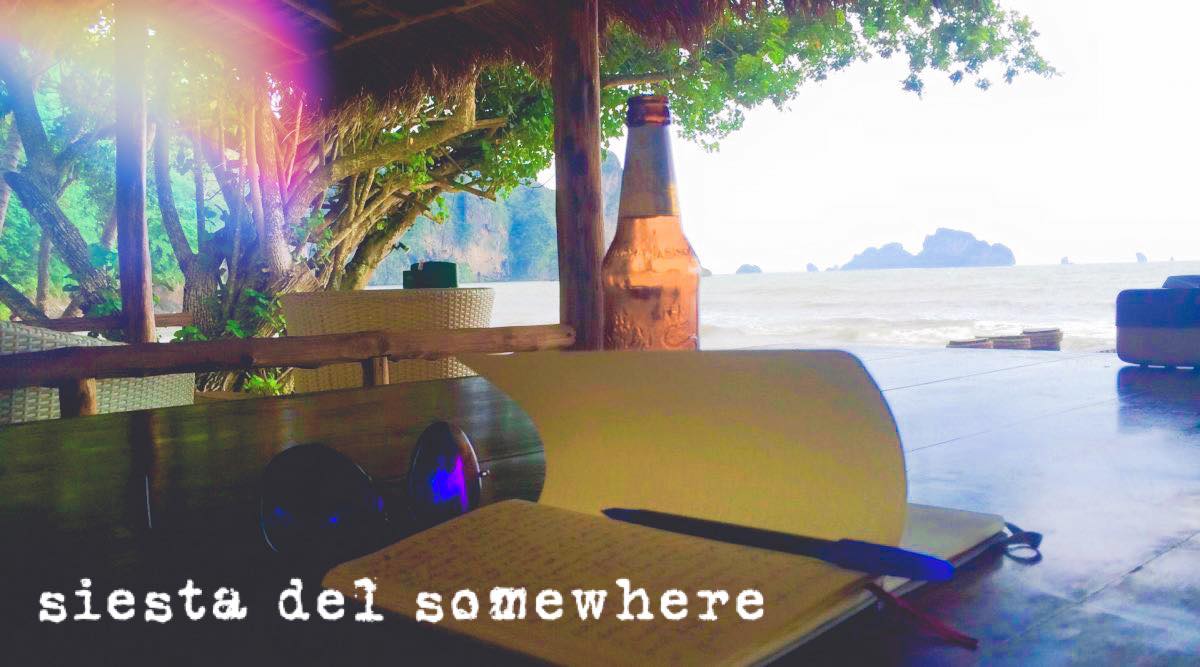

Despite being only a couple of meters in from the busy road of Route de Cienture, the courtyard of Maeve Pizza created another world. It was quiet. Incredibly quiet. All seats and tables were shaded due to the dark green foliage of vine leaves and palm trees criss-crossing and interlocking overhead. Sound became insulated here. A cockerel wandered free in the courtyard. The moon was already visible in the sky. A breeze moved through the towering forests growing on volcanic peaks and moved down towards the sea. I rested here in the silence waiting for my ferry to arrive. The owner soon brought me my pizza in due course and asked me where I was from and why I had visited Mo’orea. I explained that today was birthday and I had come to the island to do something different, to make the day memorable in some way so that when I came to look back and think what I had done to celebrate turning forty that I could think back to this day on Mo’orea and could always say I had been here. The owner called out to her husband who came outside the restaurant, bringing a bottle of vanilla rum. Both sat with me for a few minutes, toasting my birthday with a shot of red rum. The owner told me that she was from France and since childhood it had been her dream to visit Tahiti. Once she arrived here, many years ago, she vowed never to leave – and so she stayed. She said how much she loved everything here, how much she loved her life on Mo’orea and would never return to Europe. She told me that she always encouraged travellers to follow their dreams because she was grateful that she had possessed the courage to follow hers. She told me that when you follow a dream it will take you to the most amazing places.

The day had begun early. I caught the morning shuttle bus from my hotel at 8.30am to Papeete. The bus, a short journey, dropped me outside the Mairie de Papeete – a large red-roofed colonial town hall in the city centre. From here I walked down Rue Paul Gauguin, past the Tahitian Pearl Market and towards the harbour along Boulevard Pomare. There I had been instructed to look for the Agence Aremiti to buy a ferry ticket to Mo’orea. Time was ticking on and the morning ferry departed at 9.15am. After some initial difficulty I eventually found the ticketing agency near the Quai des Ferries. A return ticket cost 3,000 French Pacific Francs. I paid my money and boarded the vessel.

The journey itself was scheduled to take 30mins across the Pacific Ocean. As with most ferries there was an indoor, air conditioned deck but as it was still early and a relatively short journey I chose to sit on the smaller rooftop deck. There were a few other people doing the same – in groups and in pairs. Slowly, the ferry began to pull out of Papeete. The shops, the houses, dotted about on the sloping green ebbed away. I took out my camera and began to photograph what I could of Tahiti as it receded from view.

All week the silhouette of Mo’orea had been visible from my beach. It was a collection of dark purple, jagged peaks which rose up out of the ocean and remained there, visible in silence, throughout the day and the entire darkness of night. In his Tahitian journal, Noa Noa, Paul Gauguin wrote numerous times about the island as he sat smoking cigarettes on the sand at the day’s end, “The sun, rapidly sinking on the horizon is already half concealed behind the island of Morea [sic] which lays to my right. The conflict of light made the mountains stand out sharply in black against the violet glow of the sky.”

There is something so magical about watching an island emerge as you voyage towards it across a body of water. Its mystery fades as you approach; patches of green slowly become distinguishable, individualised trees rising up towards sunlight, while conical mountains and peaks take form and character. Around Mo’orea was a visible reef, circling the island like a barrier, distancing it from the ocean and ensuring its waters were shallow lagoons alive and vibrant in gem-like colours. A clear pathway from the deep Pacific funnelled through a break in the coral, allowing dark blue waters and the ferries from Tahiti to berth at Quai de Vaiare. As the ferry slowed and steered in to dock at Mo’orea, a tall Polynesian man broke rank from a group of friends who had been on the roof deck and approached me. Behind him a car park with a thin line of small shops came into view. For the duration of the journey, I had been photographing and writing in a small, black moleskine notebook as many impressions as I could – of Tahiti, of Mo’orea, of the endless desolation of the Pacific Ocean and the way sunlight seemed to dance on its flat surface; I had done this so I would never forget these moments. The man, wearing mirrored sunglasses, came closer and became more imposing the closer he got – he asked me if I was a journalist. I shook my head and answered, ‘traveller.’ He smiled, nodded and said in English, “Welcome to my island.”

Once on Mo’orea I made my way to a Shell Petrol Station near the Quai. It was here I had been told to meet someone from a scooter/motorbike rental company who would give me a bike hire for the day. The guy was there waiting for me. The price had been agreed the day before, so I paid in cash and signed documentation, was given a phone number should something go wrong and told to return the bike with a full tank of petrol. The speedometer was broken, but that was fine I was told: just don’t speed. There was enough fuel in the bike to drive it around the island; the return ferry back to Papeete departed at 2.45pm so there five hours to enjoy.

There was only one road – the Route de Cienture – which circumnavigated the outer edge of the island. For the duration of that ride around Mo’orea, orbiting the volcanic peak of Mount Tohiea, the mountain was always on my left and the Pacific Ocean on my right. There was no real plan in mind, other than to use the time available to me, to follow my nose, to maybe find a beach to swim, to just journey and see what happened. All I had was one of those free tourist maps that somehow ends up in your possession. Fortunately the one I had was well-detailed. Moving off from Vaiare, I figured I could drive around to the north of the island and see the two bays – Baie de Cook and Baie de Opunohu (the map indicated a beach nearby). Both were beautiful in their appearance and serenity, the quiet lapping waters milling about in coral shallows, catching perfect shadows of overhanging palm trees. Sandwiched between both bays was a road veering off the circle route and climbing some 240 metres up towards a lookout (Le Belvedere). I chanced a detour up, which was steeper than anticipated along a zig-zagging path which kept rising as my gears dropped. The view from this lookout was worth the climb and took in the coloured waters surrounding Mo’orea, the settlement of Paopao, the surrounding mountainside and forests; it was something magical.

On journeys such as these, time has a tendency to operate differently to when experienced in routine. What had seemed like a couple of hours was barely that; any concerns I had to remain close to the ferry quay – gave way to me deciding to keep on driving. It was hot, and while I had wanted a swim to cool off, once moving on the bike I barely noticed any heat. There was enough petrol in the tank and, I calculated, enough time to spare to keep on going, to push on for a full circumnavigation of the island. Coming down the hill from Le Belvedere, I turned left and opened the throttle. Names and villages rushed past me, Papetoa, Tiahura, Te Nunoa, Varari, Ha’apiti; the road was flanked by row upon row of palm trees as I sped past. While I drove around my map, using villages as landmarks, reassurance remained in having Mount Tohiea on my left and the Pacific blue on my right. While time was on my side, occasionally I would stop and switch off the engine to just absorb what beauty I saw and witnessed on the island. Sometimes it was just enough to stand beside giant palm trees watching the wind move through them, or to listen to the breeze touch the coral lagoons. Near Vaianae I watched an old man walk across a flat patch of submerged reef to cast a fishing line out into the deeper blue. On reflection, I wish I had written these observations down and described them in detail; I should have written those moments down because I knew (as I know now) the chances of me ever returning to Mo’orea in this life would be next to nil. I could have written about how happy I had felt riding around that island, the utter freedom I experienced through archways of palm trees, accompanied by ancient volcanic peaks rising up to the clouds. I could have written about those emotions, to just have had a record to read right now but in all honesty I was too busy having fun. I was lost in the moment. I experienced such freedom in the anonymity of knowing that no one else on this planet knew where I was at that precise time. Perhaps committing those emotions into words may have diluted the feelings I still have from that day.

The road continued down to the southern tip of the island, past Atiha, before turning sharply north (leading back to the ferry harbour at Vaiare). As I approached the village of Maatea, my day had accumulated close to four hours on the bike. I can remember feeling a particular kind of sadness knowing that the adventure had (almost) run its course, yet it was countered with a buoyancy in having done this and enjoyed it. Stopping at the side of the road, I took in the silence for one last time before I surrendered the bike. As I took the last of my photographs a young man on a motorbike (no helmet), emerged out onto the Route de Cienture from an uncovered track. He stopped at the junction. He looked my way. For some unknown reason I waved. The driver waved back, then revved his engine several times before pulling out onto the empty road and headed to Vaiare. As he gained speed he lifted the front wheel of his bike up off the road, turning the handlebars as he shot off into the distance. A long trail of white smoke tumbled in the air. Within fifteen minutes I would be back at the Shell Petrol Station (next door there had a restaurant called Maeve Pizza which was opening for breakfast as I had set off).

As the ferry pulled out of Mo’orea, I noticed the colour of the water in the Quai de Vaiare was teal, an opaque teal. On the ferry back I slept most of the way – choosing to sit inside the air conditioned deck. Voices spoke around me. Some in French, some in Tahitian. I understood nothing but every word sounded divine. I felt happy. I remember watching a coconut floating out to sea. It travelled alongside us as we voyaged into the deep blue. Then my eyes fell heavy and I slept to Tahiti.

*